Vanitas:The Palermo Portraits

Matthew Rolston, Untitled (Long Face), Palermo, 2013.

From the series Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits

© Copyright Matthew Rolston. All rights reserved.

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Photographer Matthew Rolston has forged a career transforming celebrities into icons by suspending their youth forever. His idealised portraits of Cyndi Lauper, Beyoncé, Madonna, et al (there are not many he hasn't photographed or filmed) capture their moment in the sun and reflect our cultural obsession with youth. Glamour is his stock in trade. Perfect creatures with alabaster skin resemble the vintage perfection of Rolston's own heroes of photography: George Hurrell, Irving Penn, and Richard Avedon. The stars in these pictures are forever. They don't die.

Matthew Rolston, Cyndi Lauper, Headdress, Los Angeles, 1986

From the series Hollywood Royale: Out of the School of Los Angeles

© Copyright Matthew Rolston. All rights reserved.

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

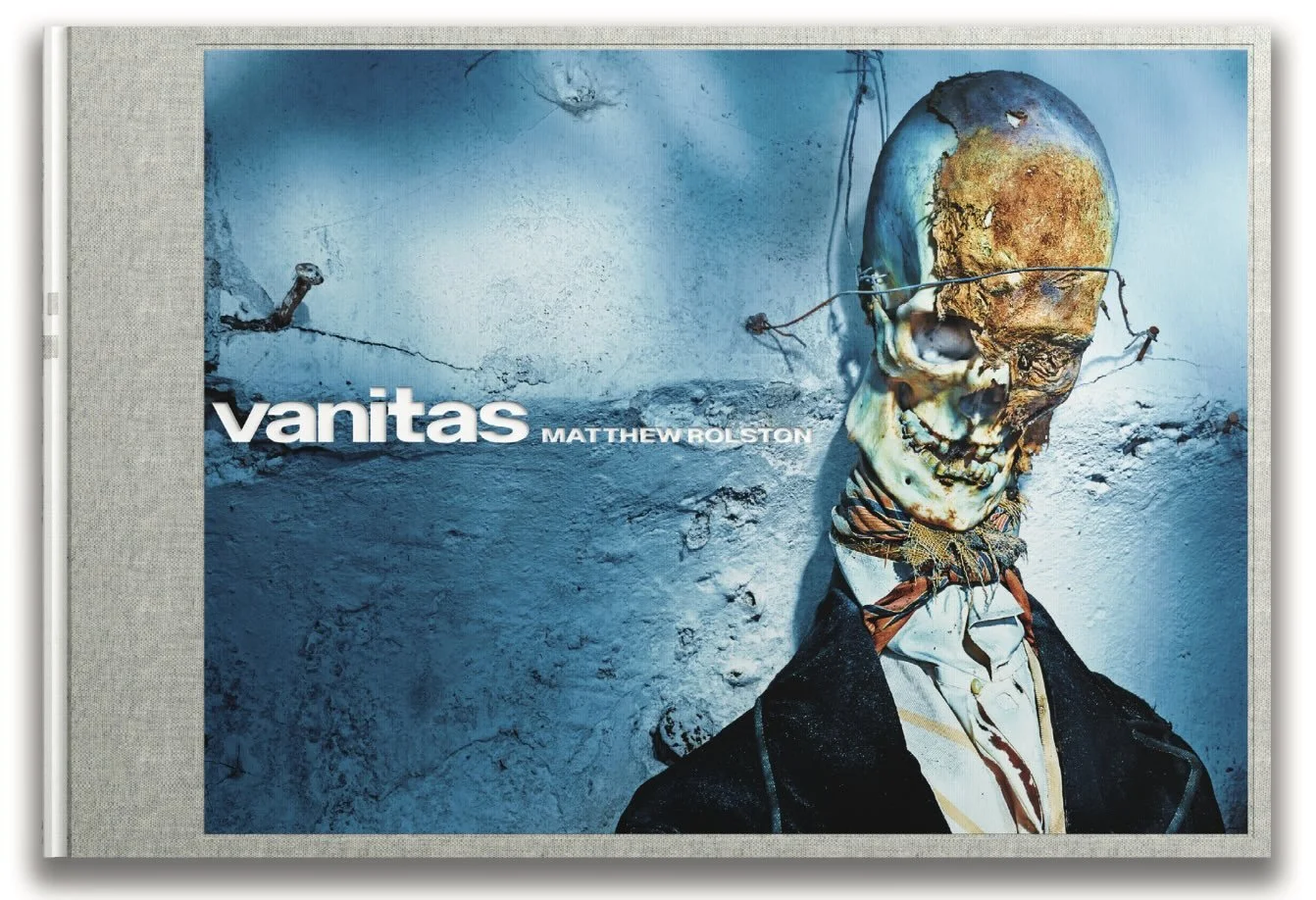

Rolston's stated purpose with artmaking is to "pose questions about the things that make us most human." In his latest project Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits, he asks the ultimate questions: where did we come from, why are we here, and where are we going? Coming full circle, Rolston has turned his lens away from creating human supernovas and instead has cast his gaze on the decomposing corpses of the renowned Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Sicily.

"…So we look at death all the time. our entertainment is brimming with depictions of death and violence, but none of it is real," he writes in a journal entry that opens his book, "THIS is real. REAL death is off-limits in our culture. do we deny the existence of death in order to live? i am here to look at death square in the face, to discover the reasons for our denial."

When asked what the Palermo catacomb made him feel about death, he answered, "profound sadness for all of us who are not ready to face the inevitable." Rolston experienced a crushing realisation that Westerners worship youth (of which he sincerely acknowledges the part he has played as a myth maker) and how miserably ill-prepared we are for death. All of us must meet our maker, but we are unlike other cultures, we have not nurtured a relationship with death as much as life.

Matthew Rolston, Untitled (Wired III), Palermo, 2013.

From the series Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits

© Copyright Matthew Rolston. All rights reserved.

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

In the 16th century, it was only the church friars who were entombed in sackcloth in the catacomb below the Church of Santa Maria della Pace in Palermo, but by some strange alchemy, the friars' bodies did not decompose. It was pronounced a miracle. The wealthy inhabitants of the surrounding area wanted a piece of eternal afterlife and so were buried in their finest clothes of silk and velvet and wired into an upright position in the hope of fast-tracking their ascension into the afterlife.

Rolston spent an intensive period of research and planning before being allowed access to the catacomb for only a single week. After closing time, Rolston and his team entered and worked through the night photographing the mummies. One profound moment was the realisation that a mound of dust resting on a shoulder of one of the inhabitants was in fact decay. "The dust on his shoulder was his face falling off. Over a 150-year period. The particles we were breathing were in some ways, the decomposing flesh of these mummies," says Rolston, describing this moment in his documentary film of the Vanitas project.

Of the 8,000 decaying individuals buried in the catacomb, Rolston photographed 70 of the mummies. He edited his series to 50 portraits for the Vanitas monograph and ultimately chose only ten to be produced as fine art prints. The dignity and care that Rolston gives to his mummified subjects is equal to any of his past fine art photography projects. He treated the ventriloquist dummies in his Talking Heads series and the participants of the Pageant of the Masters tableaux vivants in his series Art People with the same thoughtful approach; they all got the goddess treatment, and everyone is important when Rolston favours a subject.

Matthew Rolston, Untitled (Scream), Palermo, 2013

From the series Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits

© Copyright Matthew Rolston. All rights reserved.

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

The juxtaposition of rotting flesh and beauty compels and repulses. These are beautiful images of a grotesque subject. Life and death dance. A distorted face appears to scream, but that expression is actually the result of hundreds of years of slow decay and the effects of gravity; somehow, this horror is made beautiful!

Using colour and skill, Rolston, through the use of theatrical lighting gels, utilised three separate wavelengths of light. He coined the term "expressionistic lighting," to describe a signature style of illumination, one that bathes his subjects in intense waves of surprising hues of yellows, greens and golds, all against an intensely bluish-cyan background.

The palette Rolston has chosen is drenched in meaning. The blue tones that spill across all the backgrounds is a colour powerfully associated with the Catholic church. As art historian and photography critic Philip Gefter writes about Rolston's work in his essay Eros and Thanatos, “…Yet, these photographs are imbued with the color palette of the artist, one he refers to as ‘the colors of the bruise’, a soft pastel lighting that, paradoxically, invites the eye to relax even in our discomfort at confronting the face of death; these photographs are accented with an intentional ever-present ‘Marian blue’, a color in Catholic iconography associated with purity, serenity, and the heavens, qualities attributed to the Virgin Mary, and which Rolston chose after observing it in the Sanctuary of Santa Rosalia in Palermo, the blue as radiant as a crystal clear sky seen through stained glass.”

The Vanitas prints are offered as unique objects, more in the tradition of painting than photography. Standing before them, you understand why.

Matthew Rolston, Untitled (Child I), Palermo, 2013 (detail)

From the series Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits

© Copyright Matthew Rolston. All rights reserved.

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Most people live in denial, and it's only upon witnessing a tragic accident or watching a loved one slip away that the horror of death is made real. There are those who are compelled forward in their lives by an ever-present fear of death; the four horsemen hover at the corners of their dreams and stalk their every waking moment.

The Vanitas monograph’s foreword is an edited excerpt from cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker’s 1973 book The Denial of Death, here entitled Humanity’s Existential Dilemma. He wrote, ‘…As the Eastern sages also knew, humans are worms and food for worms. This is the paradox: we are out of nature and hopelessly in it, we are dual, up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill marks to prove it. Our bodies are material fleshy casings that are alien to us in many ways - the strangest and most repugnant way being that they ache and bleed and will decay and die.’

There’s no solace to be found in Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits. Rolston doesn't have answers about what's on the other side, but he insists we join him in facing death squarely in the face. What he does offer is a necessary moment of meditation.

Matthew Rolston, Untitled (Rainbow), Palermo, 2013

From the series Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits

© Copyright Matthew Rolston. All rights reserved.

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

THE FINER DETAILS

Matthew Rolston is a beacon of light for his students at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, where he teaches and helps them navigate the coming AI revolution. Rolston is an alumnus of the famed college and has been honored with its Lifetime Achievement award. The first unveiling of the Vanitas exhibition was at ArtCenter; a monumentally sized triptych with an accompanying soundtrack and short film.

Four individual exhibitions and talks are rolling out across Los Angeles this month and next, timed for Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead. Nothing Matthew Rolston does is ever without deep thought. These presentations introduce Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits as a 'mostra diffusa', an exhibition intentionally distributed among multiple venues. This approach reflects a conscious departure from the contemporary conventions of exhibition production, recalling art historical traditions in which singular works were presented in isolation.

To find out the calendar of events, click on the link below.

Printed in vivid color on rich clay-coated stock, The Vanitas monograph, an oversized publication, features fifty of Rolston’s portraits. This first printing is limited to five hundred copies. The publication includes texts from the artist, in addition to an introductory essay by American author, photography critic and journalist Philip Gefter and a forward excerpted from cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker's seminal 1973 work The Denial of Death.

Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits by Matthew Rolston. Monograph, front cover, Nazraeli Press, 2025

There is so much more to explore. Please visit the following links to dive in deeper to Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits.

Watch the film here, explore who influenced the project here, listen to the podcast here, and find out more here

very laboratory